Unleashed: Pets in the Age of Austen

- Q&Q Publishing

- Jan 11, 2023

- 5 min read

By Lucy Marin, author of The Truth About Family

Many of us have beloved non-human family members. I have two feline fur-babies, and I decided to include my love for them in The Truth About Family, which I began to write during the difficult days of 2020. Having a purring cat or two beside me was a comfort, as it has been at other times in my life.

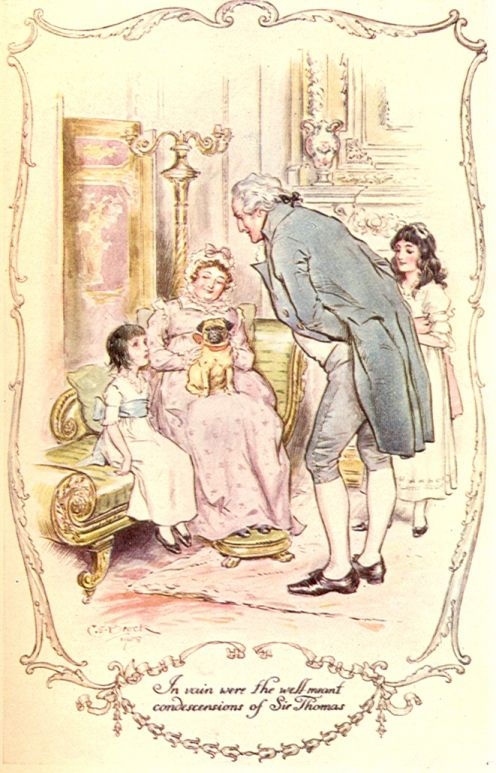

Jane Austen did not talk about pets as such in her novels, apart from Lady Bertram’s pug in Mansfield Park. That doesn’t mean animals aren’t present in the lives of her characters, of course, or that she did not share her home with cats or dogs, although she may not have had any she considered companions; instead, they might have been working animals.

During the Middle Ages, cats were seen as demonic and associated with witchcraft, although as time passed, they and dogs were kept by humans as working animals. Cats helped with pest control (which may have been why they were first domesticated in China); but dogs could perform other work, too, including herding, hunting, and security. In their role as pest controllers, cats and dogs were kept in homes, businesses, other buildings—and aboard ships, from which they were introduced to other countries by Europeans as they settled the world.

Attitudes towards animals and our relationship to them began to evolve during the Age of Enlightenment during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Although humans had been living with animals for thousands of years by this point, it was only during this era that the concept of keeping and loving animal companions became widely accepted. While today it is perfectly normal to keep pets, during Jane Austen’s time, you would find this viewpoint as well as its opposite—that is, that keeping pets was wasteful and even unseemly. Wealth certainly made it easier to keep animals only for the pleasure of having them, but people from all walks of life were likely to have animals both to perform work and provide companionship.

During the Regency, cats and dogs kept as pets likely slept in the house (especially cats as dogs might have been relegated to sleeping in the stables). They might share a room, even a bed, with their human(s), and in larger houses, might even have their own room! There was furniture designed specifically for pets, and cats then, as now, would have cushions on window seats, offering them tempting glimpses of the outside world, and baskets or boxes with blankets in which to sleep. Rudimentary litter boxes were filled with sand or soil, or cats might be able to access the outside through a window or cat door. People could obtain collars with bells for their wandering cats to protect unsuspecting birds. Cat mint, aka catnip, is native to Britain, and by the Regency era, people knew that cats liked it, so it was likely grown for pampered pets.

In wealthier homes, dogs might have been walked by servants, who also likely were responsible for grooming—including flea control, which sometimes involved a comb dipped in kerosene. There were professional dog groomers in London and other large cities, too, for those who could afford them.

Depending on the economic status of the home, cats and dogs might simply be fed scraps from the family’s meals. Food might be specially prepared for them, too; there were ‘dog meat’ and ‘cat meat’ men in the wealthier parts of large cities who, as the name implies, sold meat intended for dogs or cats from carts. Butchers would be another source of meat for domestic animals, but there was no commercially available pet food until the 1840s.

In The Truth About Family, Elizabeth is an animal lover, and those she comes across—such as Darcy’s dogs and horse—respond to her. At the time of the story, she no longer has a pet of her own, but she talks about her cat, Dotty, who was a gift from her foster brothers—Viscount Bramwell and Colonel Fitzwilliam—when she was twelve.

There is recent research suggesting that animal companionship (and exposure to nature) has psychological benefits, and I imagine it was true for Elizabeth. Although results are mixed, some studies show that pets can reduce stress and ease loneliness. Elizabeth’s little Dotty did that for her, acting as a friend when Elizabeth needed one. I used my darling Cherry as inspiration for Dotty. This is Cherry as a baby--she’s thirteen now--and the spots on her tummy are what led Elizabeth to call her furry friend Dotty. (Not coincidentally, Dotty was the name I gave a hamster I had in childhood.)

Because Ginny gets jealous easily, here she is showing off her markings. (She’s now eleven.)

The British royal family was, and is, known for its love of dogs. In the seventeenth century, Charles I popularized the King Charles spaniel. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert kept a large collection of domestic dogs, and commissioned Sir Edwin Landseer to paint their favourite pets.

Dog breeds have changed quite a bit since Jane Austen’s time, which I always found very interesting. For example, English bulldogs have been bred to have saggy jowls and a stocky body, or pugs, which today have flatter noses and bigger eyes than those in the early 1800s. In The Truth About Family, Darcy favours Great Danes. They, too, have been altered by breeding. The ones Darcy had likely weighed around 55 kilos (120 lbs); today, male Great Danes (like the one Darcy had as a boy) can reach 80 kilos (175 lbs)! Other common dog breeds during the Regency included Pomeranians, terriers, spaniels, Italian greyhounds, and whippets. Most pet dogs at the time were mixed breeds. As for cats, common breeds were domestic shorthairs, tabbies, Manx, and more exotic types such as Persians and angoras.

One might obtain their animal companions via breeders or people selling animals in various locations—including coffee houses!—by gift, or simply taking in a stray. There were no pet stores as we know them today until later in the nineteenth century, and those that did exist mainly supplied birds and bird supplies.

Veterinary care was rudimentary. In 1791, thirty years after the first known veterinary school opened in France, the Royal Veterinary College (then called the Veterinary College, London) was established. The initial class of four students (no women attended until the 1920s) focussed chiefly on large animals, such as horses and cattle.

Of course, many of the individuals treating animals might have little formal training. In London or other major population centres, you might find the rare small animal doctor. Wealthy pet owners might rely on their own doctors to tend to their animals. Others with some medical expertise—including farriers, horse and stable masters, animal breeders, midwives, and apothecaries—might provide veterinary care as well.

Of course, people had a variety of animal companions beyond cats and dogs. Native songbirds, captured from the wild, and exotic birds, such as parrots, brought to England by explorers, were kept in homes. Other exotic species also came to England, including Guinea pigs, monkeys, and kangaroos, as well as large animals such as elephants and big cats, which would be kept in public or private menageries. These two lovelies are Guinea pigs Holly and Hazel, my daughter’s late little darlings.

Local species were also kept as unusual pets, including foxes, badgers, rats, mice, hedgehogs, squirrels—it seems that people were content to make pets of virtually any animal. I certainly understand the impulse, readily acknowledging how much my life has been enriched by sharing my home with other animals!

Sources:

Boehringer Ingelheim The Brief History and Journey of the Domestic Cat (n.d.) https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/animal-health/animal-health-news/history-cats

Boehringer Ingelheim The human-dog relationship—a historical perspective (n.d.) https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/our-responsibility/animal-health-news/human-dog-relationship-historical-perspective

Cornell, Louisa (2022). From canines to the ridiculous: Pets in Regency England. The Regency Fiction Writers [online course]

Lewis, T. (2018, 28 April). Here’s what popular dog breeds looked like before and after 100 years of breeding. https://www.sciencealert.com/what-popular-dog-breeds-looked-like-before-and-after-100-years-of-breeding

NIH News in Health (2018, February). The power of pets. Health benefits of human-animal interactions. https://newsinhealth.nih.gov/2018/02/power-pets

Royal Collection Trust https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/trails/royal-pets

The Royal Veterinary College (2022). History. https://www.rvc.ac.uk/about/the-rvc/history

Utaraité, N. (2021). Here are 18 photos showing dog breeds today vs. 100 years ago. Bored Panda. https://www.boredpanda.com/dog-breeds-100-years-ago-and-today/

Wills, M. (2017, 28 January). The invention of pets. JSTOR Daily. HTTPS://daily.jstor.org/the-invention-of-pets/

Comments