Regency Explorers: Daring Expeditions and Treacherous Voyages

- Q&Q Publishing

- Oct 15, 2025

- 6 min read

By Ali Scott, author of Into The Woods

“If adventures will not befall a young lady in her own village, she must seek them abroad.” Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey

In my latest story, Into the Woods, Elizabeth has a godfather—the wealthy explorer, Mr Artur Vanderbeck. With no other living relatives or godchildren, it is assumed (amongst various ill-informed members of Meryton society) that he will provide Elizabeth with a dowry. A man of consequence, Mr Vanderbeck plays a pivotal role in securing the happiness of our beloved Darcy and Elizabeth, but who were the true adventurers of the Regency era?

Alexander von Humboldt: “The most dangerous worldviews are the worldviews of those who have never viewed the world”

Born to a wealthy Prussian family in 1769, Alexander von Humboldt became an influential figure in the world of scientific exploration. Blessed with a remarkable memory, Humboldt could recall the minutiae of his research many years later. This extraordinary skill permitted him to compare observations that he had made at different points of the world, decades apart. One colleague would say that Humboldt was able to ‘run through the chain of all phenomena in the world at the same time.’

As a young man, he visited London, and witnessed the River Thames transform into a ‘black forest’ of masts, with vessels arriving from the further corners of the globe. Due to family circumstances, he could not pursue his dream of foreign exploration, but, as Humboldt explains: “There is a drive in me that often makes me feel as if I am losing my mind.”

Upon returning to Germany, Humboldt channeled this fervour into his studies, enrolling at a prestigious mining academy in Freiburg and completing a three-year course within eight months. He swiftly rose to the position of mining inspector. This role required him to travel thousands of miles to investigate shafts. During this period, he invented a breathing mask as well as a lantern that could operate in oxygen-poor mines.

After his mother’s death, Humboldt received a substantial inheritance, and now, unshackled by the burden of familial expectation, he was free to travel the world. The only problems, however, were where to go and how to get there. Political conflict meant that passage to foreign shores was fraught with difficulty. Eventually, Humboldt secured a passport from King Carlos IV of Spain. Forty-one days after they left Europe, Humboldt and his expedition partners arrived at New Andalusia (now Venezuela). Humboldt’s first action when stepping ashore was to plunge his thermometer into the glorious, white sands. ‘37.7°C,’ he meticulously observed in his notebook.

The expedition took him into the densest corners of the Amazonian jungle, trekking through the darkness lit only by fireflies. Despite being unable to swim, Humboldt canoed upstream against powerful currents for two months, narrowly avoiding crocodiles. He traversed the treacherous Quindo Pass, considered the most dangerous trail in the Andes, the muddy path sometimes only eight inches wide, at one point hiking barefoot after his shoes were torn to shreds by bamboo. All this Humboldt survived, without ever knowing if he would see his family again, or if his precious equipment and research would remain undamaged.

More than five years later, he returned to Europe as a celebrated naturalist. He brought back nearly 60,000 plant specimens, of which 2,000 species were hitherto unknown to Europeans—-a significant contribution when taking into consideration that only about 6,000 species of plant were known at the time. His legacy was vast; in Berlin, he taught a course on physical geography and once gave a lecture on the subject to an audience of over 1,000. Amongst his notable admirers was Charles Darwin, who noted, when on his own expedition ship, the Beagle: ‘I spent a very pleasant afternoon lying on the sofa….reading Humboldt's glowing accounts of tropical scenery. Nothing could be better adapted for cheering the heart of a sea-sick man.’

Humboldt’s observation, that, ‘in this great chain of causes and effects, no single fact can be considered in isolation,’ remains pivotal in humanity’s understanding of the natural world. He describes a traveller, as ‘a historian of nature,’ which may serve to explain his compulsion to observe and record all the natural phenomena he encountered. But, Humboldt’s love of exploration was more a mere need than scientific exploration. He delighted in all that he witnessed, writing: ‘What speaks to the soul escapes our measurements.’

The controversial Sir John Ross: Daring pioneer or scheming opportunist?

For centuries, the discovery of a westbound sea route linking the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean had long eluded explorers. Over time, the drive to discover this fabled Northwest Passage intensified: in 1745, an act of Parliament offered £20,000 reward to any British subject who found their way through the treacherous Arctic archipelago.

Born in West Galloway in 1777, John Ross joined the Royal Navy at the age of nine. The son of a minister, Ross rose to the rank of commander without any patronage. In 1818, he was charged to find the Northwest Passage, and set off from London on the Isabella, with his second-in-command, William Parry, the captain of the Alexander.

Their journey was to be impeded by the adverse conditions. Once, when stuck in the ice flows, the ships collided, causing significant damage. As the ice drifted apart, it became clear that the ships’ anchors were entwined, threatening to pull the vessels apart. Eventually, the danger passed, and the crew were able to make frantic repairs. They renewed their journey, but were to stop again at the sight of figures waving from across the ice. Believing them to be shipwrecked sailors, Ross sent out John Stackheuse, the expedition’s indigenous interpreter, and were informed that these native people were catching narwhals. Ross and Parry met the group in full dress uniform, learning that this band of hunters had never encountered any other human being before, ‘...having until the moment of our arrival, believing themselves to be the only inhabitants of the universe.”

They continued on their journey, venturing into Baffin Bay, Ross’s Isabella some nine miles ahead of Parry’s Alexander. It was here that Ross claimed to see a mountain range that blocked their path. He named them the Croker’s Mountains, after the First Lord of the Admiralty. Parry and his officers would later dispute this ‘discovery.’ The controversy around Ross’s claim tainted his reputation for the rest of his career.

In October 1818, it is thought that Ross lost his nerve and turned back. Initially, he returned to Britain as a hero, but soon discrepancies were found in Ross’s research. Worse still, it was alleged that the magnetic observations were taken by Ross’s nephew, not by Ross himself. In 1819, in a separate voyage to find the Northwest Passage, Parry disproved the existence of the Croker Mountains.

Desperate to restore his reputation, ten years after his first expedition, Ross proposed to navigate the Northwest Passage—this time by steamboat. Unable to secure funding from the Admiralty, he received a private investment. In 1829, he set off in the Victory, a converted mail packet. Ross and his crew would spend four years in the Arctic. Whilst there, they conducted many expeditions and Ross’s nephew would reach and claim the magnetic north in the king’s name.

As their supplies dwindled, Ross and his crew were forced to abandon the Victory and make their way across the ice on foot, transporting the Victory’s two smaller boats and 2,000 lbs of provisions over 300 miles. They reached Fury Beach, and within twenty-four hours, constructed a huge tent from timber and sails, called Somerset House. Ross attempted to sail from this base, but was forced to turn back by the impenetrable ice.

After spending a harsh winter at Somerset House, Ross decided to make another attempt at crossing the sea ice. On spotting a ship, the men launched a boat only to be hampered by the winds. On the horizon was a second vessel, and, undeterred, they doggedly rowed for an hour in its direction where they were eventually seen and rescued.

On embarking, an enquiry was made as to the name of the vessel. The reply came that it was the Isabella, once commanded by Captain Ross—a man presumed long dead. To the astonished crew, Ross introduced himself. He had been rescued by his old ship.

Redeemed in the eyes of the public, Ross was knighted on his return, and despite it not being a naval voyage, was able to secure wages of four and a half years pay for the crew. He would return to the Arctic once more, at the age of 73, in search of missing explorer Sir John Franklin.

_________________________________________

References:

Wulf, Andrea. The Invention of Nature: The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt, the Lost Hero of Science.

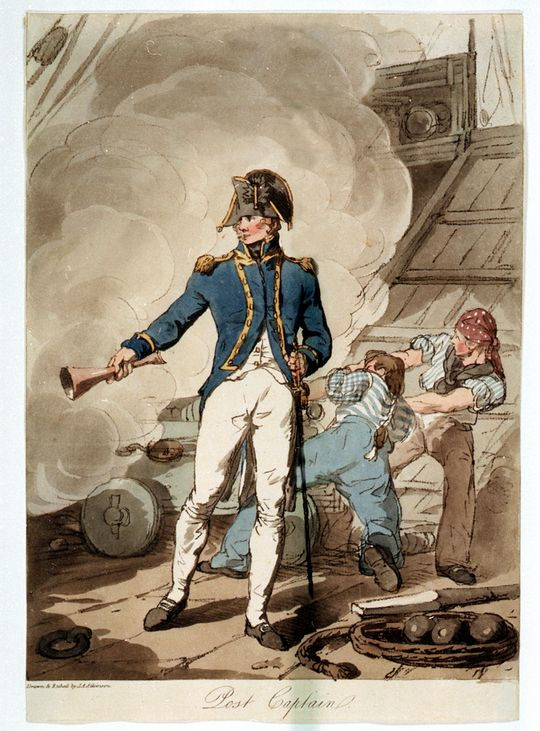

Illustrations (all public domain)

Humboldt and his fellow scientist Aimé Bonpland near the foot of the Chimborazo volcano, by Friedrich Georg Weitsch (imaginary scene 1810)

Alexander von Humboldt, by Friedrich Georg Weitsch

Andean Condor, by Alexander von Humboldt

Sir John Ross, 1833

John Ross's ship Victory under sail for the last time in the Gulf of Boothia, 1832

A Remarkable Iceberg, by Charles Hamilton Smith, July 1818

The rescue of John Ross and his crew in 1833, engraved by Edward Francis Finden, 1840

Comments