Hero or Villain? The Conundrum of a Man in Uniform

- Q&Q Publishing

- May 16, 2024

- 8 min read

By L. M. Romano, co-author of Without Vanity Or Pride

“…he was happy to say [he] had accepted a commission in their corps. This was exactly as it should be; for the young man only wanted regimentals to make him completely charming.”

-Pride and Prejudice, pg. 62

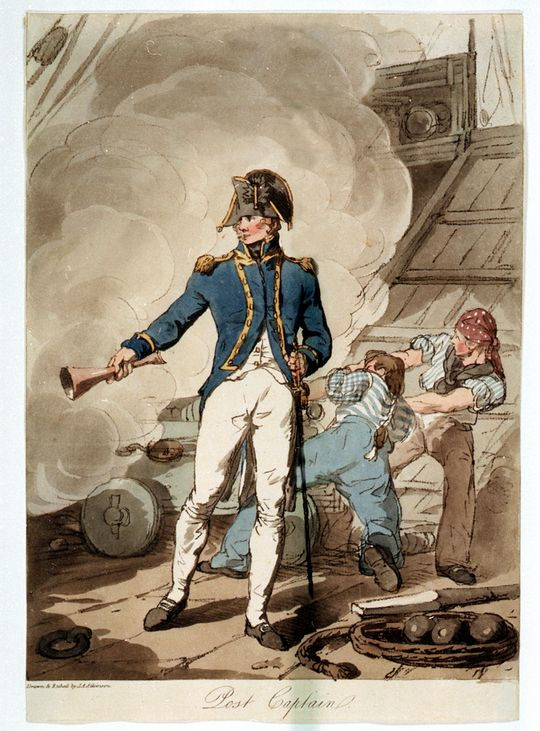

Even from a modern perspective, it is hard to deny the appeal of a man in uniform. Honor, duty, discipline, and the desire to protect the defenseless are all somehow imbued into the sharp lines and dashing colors of military regalia. A soldier’s attire singles him out as one of a vast cohesive group that is collectively devoted to the nation’s protection. Yet despite the prestige afforded to a man who dons the attire of the ever-valiant soldier, it is this sameness that can deceive. For after all, the characters of men are never identical, so it stands to reason that if all soldiers are accorded the respect and esteem that a military uniform naturally endows, not all are deserving of it. There is perhaps no greater example of this in all of Jane Austen’s works than the utterly reprehensible Lt. George Wickham in Pride and Prejudice. In my latest story, Insufficient Vanity, poor Elizabeth Bennet is forced to endure the insincere attentions of her nefarious brother-in-law as he attempts to regain her good opinion after his scandalous elopement with her younger sister, Lydia.

Mr. Wickham first came to the Bennets' notice as a new recruit to the militia regiment stationed in their local town of Meryton. His charm, good looks, and easy manners, all accompanied by a dashing red coat, quickly made him a favorite amongst the local ladies of the gentry, and the Bennet ladies in particular. The question is, why was Mr. Wickham, a complete stranger, able to deceive an entire town about his character and his past so easily? In Austen’s England, was the uniform of a lowly officer in the militia enough to secure the unquestioned goodwill of the local gentry? Who exactly were the officers of the militia? Were they generally considered good prospects for marriage, or was Lydia Bennet’s desire to marry a red coat truly a flight of fancy on the part of an immature teenage girl?

To understand the answers to these questions, one must first begin with an exploration into the state of the army in Georgian England. Due to the ongoing wars with France, the English Army experienced a rapid expansion between 1792, when the number of officers totaled only 3,107, to 1814 when that number had risen to 10,590.[1] A military career was one of only a few options for seconds sons of gentleman to maintain their social status. If they did not expect to inherit the family estate, or perhaps only had an expectation of future wealth from a childless relative, gentlemen’s sons were expected to pursue a career in the church, the law, or the military. A commission in the army was typically purchased, with an ensigncy (the lowest position in the officer’s ranks) costing from £400 in a line regiment, to £1,600 in the fashionable Life Guards. [2] Some regiments were more highly desired than others, typically due to the prestige of their commander which could elevate an officer’s standing in society. Though not destined to become a great military hero, even the London dandy Beau Brummell eagerly snatched up an opportunity to join the 10th Hussars, a very popular regiment commanded by none other than the Prince of Wales himself.[3]

Wages were not very high in the army, particularly as a lower-level officer, and unfortunately the cost of the uniform and its accoutrements, coupled with living expenses, could well exceed an officer’s income. In Rory Muir’s work, Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune, Muir noted the financial insecurity officers often faced, especially in a popular regiment. “A cornet in the 15th Light Dragoons – a particularly smart and expensive cavalry regiment – was said to need a private income of almost £400 in addition to his pay if he was to hold his own.”[4] It was not uncommon for officers in the army to receive stipends or an allowance from their fathers or elder brothers, but even so, only a fairly successful officer could afford to support a family without outside assistance. Colonel Fitzwilliam’s claim to Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice of needing an heiress to support his lifestyle (and the family that would inevitably result from marriage), while seeming somewhat mercenary, was actually rather practical and explains Elizabeth’s lack of offense at his declaration. Ensigns, the rank Darcy purchased for Wickham upon his marriage to Lydia Bennet, were not encouraged to marry (more than half of ensigns were under the age of eighteen) unless they had additional income, or in Wickham’s case, money brought through marriage--provided of course, by Darcy.[5]

While life in the regular army was often fraught with danger and not particularly profitable, what of the militia? Originally formed for the defense of England should a French invasion occur, a militia man did not often risk life and limb for the security of his country – in fact, the life of a militia officer was normally mundane and rather dull. In contrast to the regular army, commissions in the militia were not purchased, as officers were simply appointed by the Lord Lieutenant of the county. There was a property qualification for officers (ensuring their status as gentlemen), however this requirement during the Regency era was often ignored due to a lack of available men, particularly for ranks lower than a Captain.[6] The property requirement should have ensured that the officers stationed in Meryton were viable marriage prospects for the Bennet daughters, but due to the Napoleonic Wars, an officer’s coat was no longer a guarantee of financial competence. Many militia officers were also employed in other professions that supplemented their income, as the duties of an officer could be considered almost a part-time employment. Henry Austen, Jane Austen’s brother, was gainfully employed in the banking industry during his stint as an officer of the Royal Oxfordshires before leaving to pursue a career in the Church.[7] Armed with an excess of charm, gentlemanly manners, and a Cambridge education (a rarity among officers[8]), a man of Wickham’s caliber would have been eagerly welcomed into a local officer’s corps. By simply donning the respected uniform of an officer, Wickham was able to conceal his unsavory past and gain a respectable social status regardless of his personal merit or previous reputation.[9] Elizabeth herself notes that Wickham’s past was easily concealed from those in her neighborhood, “Of his former way of life, nothing had been known in Hertfordshire but what he told himself.”[10]

The militia, in general, had a rather complicated relationship with genteel society during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Austen originally wrote Pride and Prejudice or “First Impressions” during the late 1790s, and it was during this period that the system of housing the militia in local counties broke down. Due to the Mutiny Act of 1690, the militia had the right to be quartered in local public houses (inns, taverns, etc.) at a high cost to the local proprietors.[11] We see this in effect in Pride and Prejudice, where the militia is quartered in Meryton – the officers residing in town, while the privates, or “foot soldiers”, were kept in a nearby encampment. When local villages could no longer house such large contingents of soldiers, the army was forced to construct barracks for their housing. This was not always a tenable solution, as Henry Austen’s time in the Royal Oxfordshire Militia shows. Encamped in Seaford, near Brighton, the newly constructed barracks for the soldiers of Henry’s regiment were not only poorly constructed, with leaking roofs and cold drafts, but the militia were also provided scant provisions. Between a diet of spoiled bread and watered-down ale and the daily physical demands of marching twelve miles there and back to Brighton for their training, it is no wonder that the discontent among soldiers grew to the point of outright rebellion.[12] The Seaford Mutiny was only one reason why most Englishmen were more than wary of a standing army. Opinions of the general worth of militia soldiers, those the officers were meant to train and oversee, was not particularly high, as demonstrated by William Cowper in his poem, “The Task”, published in 1782.

“’Tis universal soldiership has stabbedThe heart of merit in the meaner class.

Arms, through the vanity and brainless rageOf those that bear them, in whatever cause,

Seem most at variance with all moral good,

And incompatible with serious thought.

The clown, the child of nature, without guile,

Blest with an infant’s ignorance of all

But his own simple pleasures, now and then

A wrestling match, a foot-race, or a fair,Is balloted, and trembles at the news.”[13]

Contrasted with this bleak outlook of the average English soldier, the militia was also a form of spectacle for the local populace. The militia camp at Coxheath, for example, was overseen by the Duke of Devonshire and became “a magnet for sightseers both common and aristocratic.”[14] The colorful uniforms, impressive military drills, and the opulent lifestyle of the camp’s leadership was altogether such a stunning display that a coaching service was arranged for visitors to travel from London to Coxheath for the sole purpose of visiting the encampment.

In such a setting as this, where spectacle combined with a semblance of duty, honor, and gallantry, it is no wonder that impressionable young gentlewomen would come to fancy a handsome soldier. When a uniform both guaranteed social status and hid past deeds, it would have taken a degree of discernment to uncover which officers were worth knowing and which were not. Why look for hidden ugliness when one can enjoy the spectacle of a handsome, charming soldier on the surface? Elizabeth Bennet’s own words summarize this point quite well, “As to his real character, had information been in her power, she had never felt a wish of inquiring. His countenance, his voice, and manner, had established him at once in the possession of every virtue.”[15]

Sources:

[1] Rory Muir, Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune: How Younger Sons Made Their Way in Jane Austen’s England, (New Haven, CT and London, England: Yale University Press, 2019), 245.

[2] Ibid, 245.

[3] Venetia Murray, An Elegant Madness: High Society in Regency England, (New York: Penguin Books, 1998), 29.

[4] Muir, Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune, 259.

[5] John Breihan and Caplan, Clive, “Jane Austen and the Militia,” Journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America – Persuasions, no. 14 (1992): 23.

[6] Ibid, 20.

[7] Kevin Bacon, “Jane Austen’s Brother and the Royal Militia Mutiny of 1795,” Brighton & Hove Museums, 2024, https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/discovery/history-stories/jane-austens-brother-and-the-royal-oxfordshire-militia-mutiny-of-1795/.

[8] Muir, Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune, 247.

[9] Tim Fulford, “Sighing for a Soldier: Jane Austen and the Military in Pride and Prejudice,” Nineteenth-Century Literature 57, no. 2 (2002): 157.

[10] Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, (New York: Bantam Bell, 1981), 176.

[11] Breihan and Caplan, “Jane Austen and the Militia,” 21.

[12] Bacon, “Jane Austen’s Brother and the Royal Militia Mutiny of 1795.”

[13] William Cowper, The Task and Other Poems, (London: Cassel & Company, 1899), Book IV, Lines 626-636.

[14] Fulford, “Sighing for a Soldier,” 155.

[15] Austen, Pride and Prejudice, 176.

Image Sources (all public domain):

Cornet Thomas Boothby Parkyns, 15th (or the King's) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons, 1780

Oil on canvas, signed and dated lower left 'J Boultbee, Pinx 1780', by John Boultbee (1753-1812), 1780.

A Review of the London Volunteer Cavalry and Flying Artillery in Hyde Park in 1804, unknown artist

Edmund Blair Leighton, The Wedding March

Engraving of Coxheath Camp, 1778, Jefferyes Hammett O'Neale (artist) W. Walker (engraver)

Bernard Lens III: A Volume of ten drawings of Hampton Court taken by the life - An East View of the Quarter Guard on Hampton Court Green 1733

Comments