The Life of a Regency Clergyman

- Q&Q Publishing

- Mar 9, 2022

- 3 min read

Updated: May 4, 2022

By Paige Badgett, author of Against Every Expectation

“The rector of a parish has much to do. In the first place, he must make such an agreement for tithes as may be beneficial to himself and not offensive to his patron. He must write his own sermons; and the time that remains will not be too much for his parish duties, and the care and improvement of his dwelling, which he cannot be excused from making as comfortable as possible. And I do not think it of light importance that he should have attentive and conciliatory manners towards everybody, especially towards those to whom he owes his preferment.”

- Mr Collins, Pride and Prejudice

Much of Against Every Expectation takes place in Kent, at the home of Reverend William Collins—a rector in the Church of England whose living was the gift of his patroness, Lady Catherine de Bourgh. Of course, with Mr Collins being a large part of this story, you know there will be sermon writing, and moralizing, and references to the church calendar found in the book, and yet the full picture of his life—the life of a Regency-era clergyman—is left largely unexplored.

The Church of England was the official religion of England and the Anglican version of Protestant Christianity, which was upheld by the law and financed largely by English landowners. Even Jane Austen’s father was a rector, which is likely why we find so many clergymen throughout her stories—not only are clergy an essential and expected part of gentle society, but this was also a lifestyle for which she was dearly familiar.

Like Mr Collins, who finds himself beholden to the whims and preferences of Lady Catherine, both financially and socially, the lives of clergymen were forever intertwined with peers and landowners across the country. Appointments were generally gifted due to the influence of connections as well as the prestige of one’s schooling—which begs the question of why Lady Catherine chose Mr Collins. It was much more likely she would have been saving the Hunsford appointment for the second or third son of a family member or friend—a gently-bred son who was never expected to inherit but deserved a respectable living.

Clergy in this time were not often gentlemen who were following a calling to a life of service and sacrifice but instead were choosing a traditional or expected profession—a satisfactory living that promised to keep them housed, fed, and retaining a certain level of the respect and influence for which they were long accustomed. Some were so high in the instep that they rarely were even in attendance at their own churches—employing the services of a curate.

Some rectors even held more than one living, requiring them to have curates employed to perform their duties at the various churches they served. In addition to money received per annum for their appointment, rectors could expect a parsonage to live in, tithes from their parishioners, and payments for religious ceremonies such as baptisms, marriages, and burials.

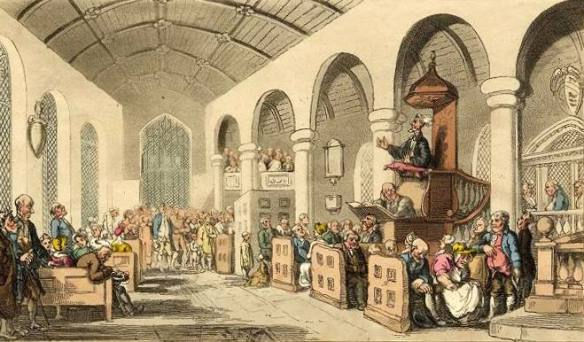

On Sunday mornings, you would have likely found Lady Catherine and her daughter sitting in a place of honor near the nave of the church (the central part of the sanctuary) in a box pew of her own design. The wealthy were often welcome to build seating how and where they liked within a church building. This ensured they had a comfortable place to sit and a location in the building that advertised their privilege, illustrating their importance in local society as benefactors of the church. Popular in the early 1800s, a box pew was often the design of choice for the wealthy in order to provide these prominent churchgoers some privacy and protect them from draughts. At the time, the thousands of churches across England were largely old and in disrepair, as well as providing no heating elements against the cold during winter. Unlike the wealthy in attendance, the “worthy poor” would share common pews or sit in a gallery.

Mr Collins would have been expected to write sermons and oversee Sunday services, but churches in this time were often locked throughout the week. Church buildings were not yet seen as places with open doors to the poor and needy as they later became. It was not through the building that he would have executed his “parish duties”; yet it was likely he would have been expected to visit the poor, the newly born, the dying, and the sick.

Whatever Lady Catherine’s reasons for choosing to grant the living to Mr Collins, one thing is clear—the rector was a place of great importance in Regency society and life in England. And I think we can all agree that the long-winded, cumbersome ramblings of Mr Collins are some of the best comedy to be found in Pride and Prejudice.

References:

Jane Austen’s England: Daily Life in the Georgian and Regency Periods by Roy and Lesley Adkins (2013)

I had no idea churches were closed during the week. Given the importance of the church at the time, I would have assumed differently. Thanks so much for the history lesson, Paige!

The history of the church is fascinating! As a Pastor myself and a woman I wouldn't have been allowed to in those days. I can't imagine locking the doors and seeing it as a place of prestige! Although, it is still true today that everyone has their favorite seat and gets quite thrown off when others sit there! Wonderful history.